On this month's Morbidly Fascinating Page:

The very first plastic surgeries attempted during WW I

IN THE ARCHIVES:

Tombstone Symbols

Weird Photos

Stuckie

Two-Faced

Hyperdontia

Preserved

Circus Curiosities

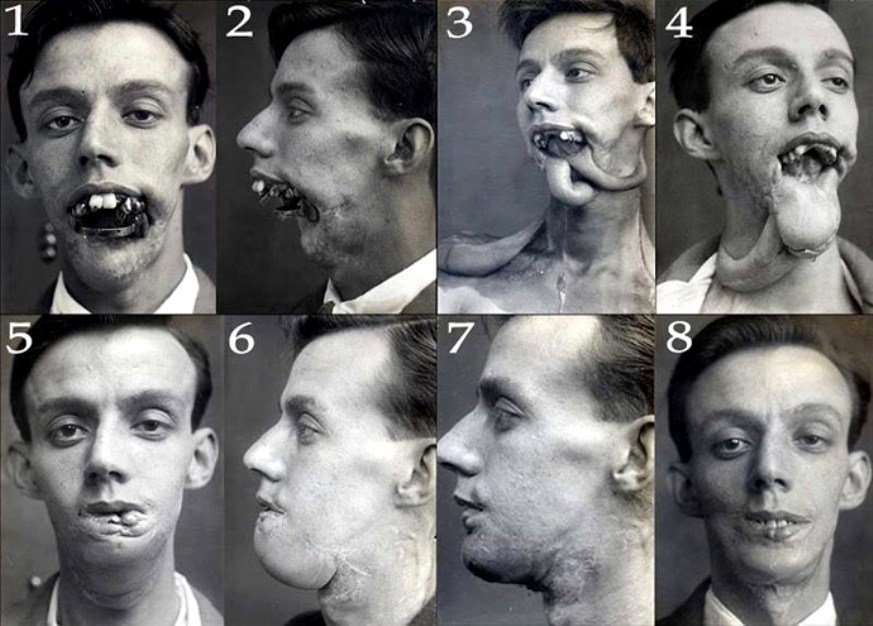

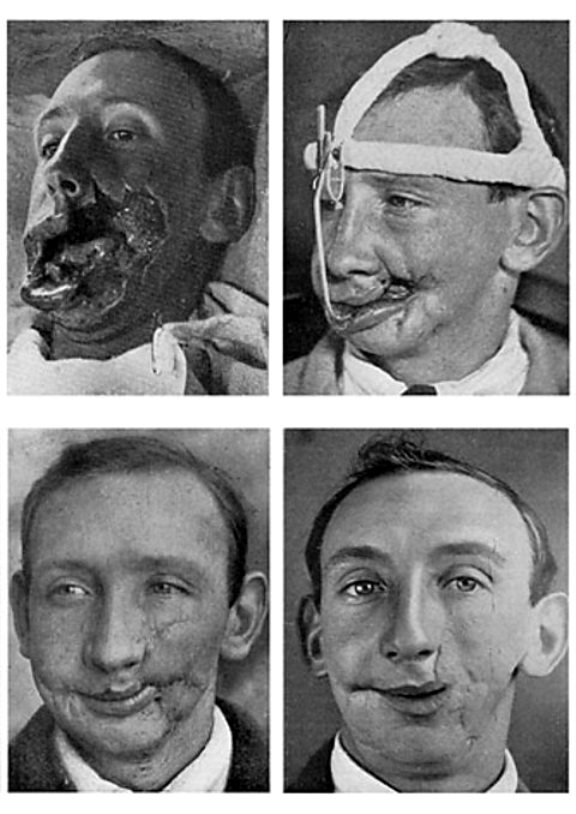

William Vicarage had lost most of his jaw in the battle and to restore it demanded extensive grafting. Vicarage’s new jaw was made from skin grafted from his shoulders, Sir Harold Delf Gillies (the first plastic surgeon) left the grafted skin attached at the shoulder and fashioned it into a tube maintaining blood flow and thus encouraging it to take to the new site. Remember, these were the days before antibiotics. Gilles named his invention the tube pedicle and it went on to become a fundamental technique of reconstructive surgery that was used in widely both world wars. I am unable to find how they grafted bones, perhaps cadaver or bovine? Or perhaps they used a rib from the victim's own body.

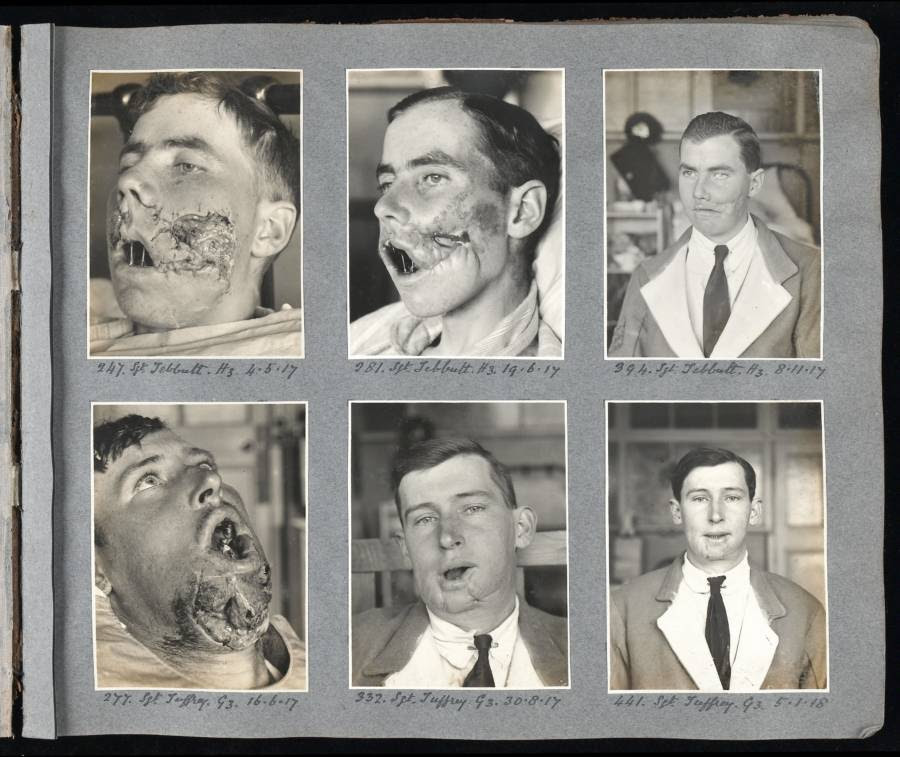

A remarkable series of images of a gunshot wound to the face. The wound must have been managed with irrigation, debridement, drainage and partial closure. Secondary repair has been done with fairly large sutures. The final picture shows remarkable healing. The scar is evident but this could be revised. We could not have done much better today considering that this was a war wound that probably occurred in the trenches, far away from base hospitals, the time elapsed from injury to definitive treatment.

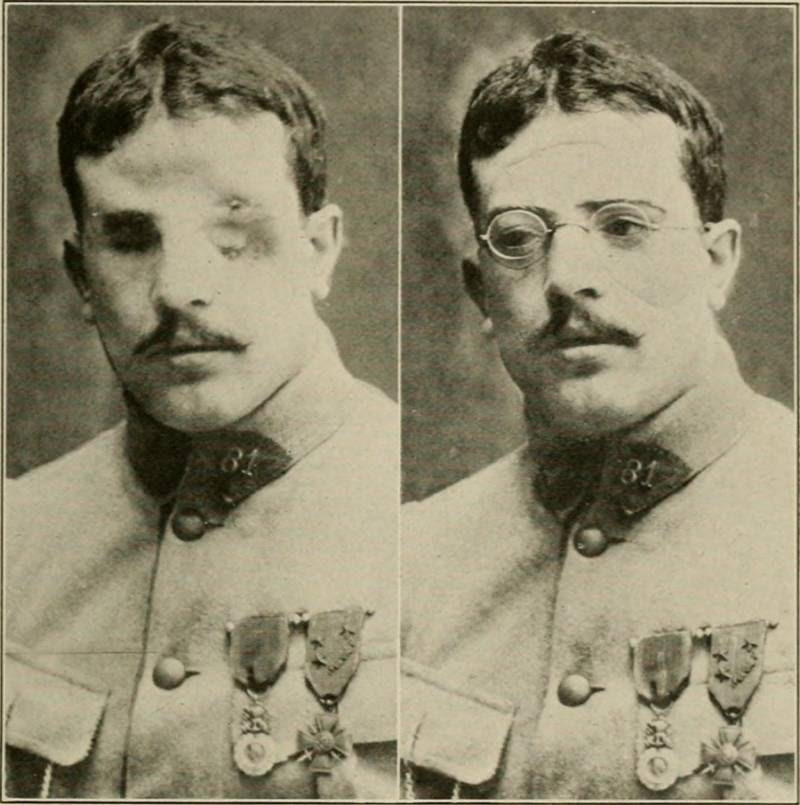

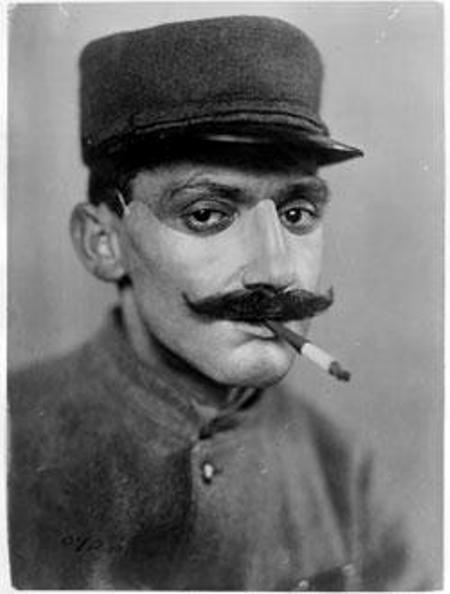

Sometimes plastic surgery was not used at all, and victims had simple casts placed on top of the injuries. The above soldier has a plaster cast inserted on top of his healed injuries for aesthetics purposes only. He was still blind. The glasses are merely for disguise. If you look closely, you can see the lines on his forehead and cheeks where the cast begins and ends.

Since Gillies could not "fix" every soldier, they also used plaster casts. Here is how they made the plaster casts. You can see the ears in the middle of the photo.

Here is a soldier wearing a complete face mask.

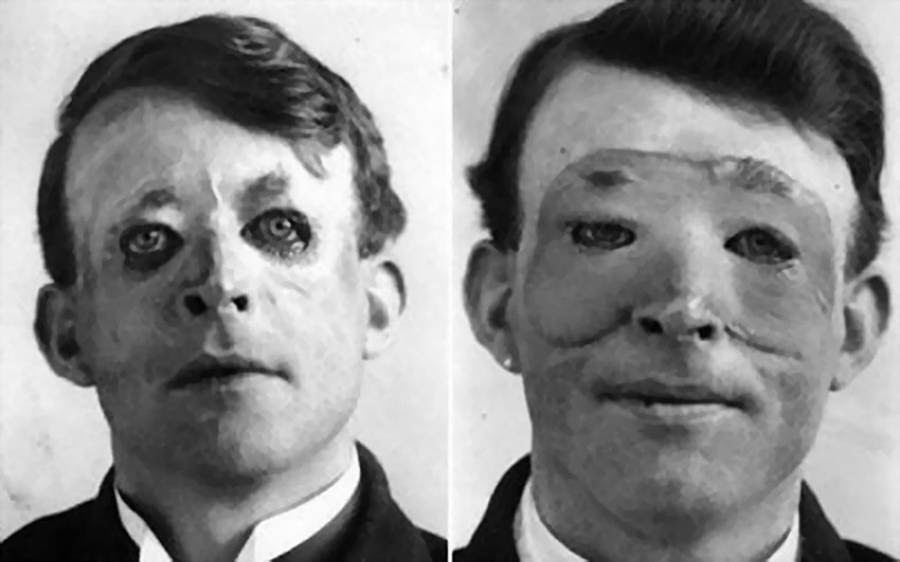

Above is Walter Yeo, the very first person to ever receive reconstructive treatment. His was a plaster cast placed on top of the injuries. As you can see, it was not very convincing.

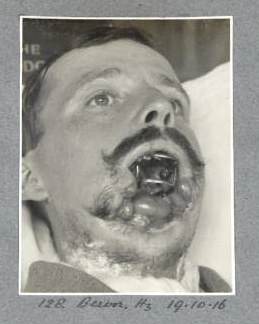

Another early surgery performed by Harold Gillies, this time in 1916 of a British soldier.

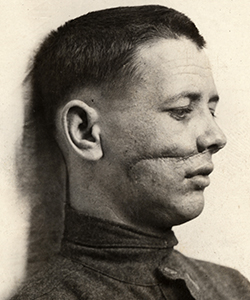

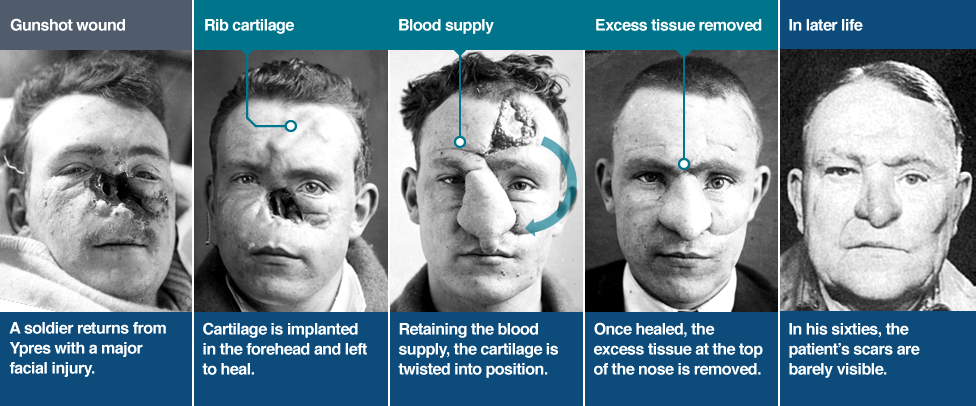

Lieutenant William Spreckley, above, was one of Harold Gillies’ biggest successes. To fashion him a new nose, Gillies hit the books and came across an old Indian idea known as the ‘forehead flap’. He took a section of rib cartilage and implanted it in Spreckley’s forehead. It stayed there for six months before it could be swung down and used to construct the nose. From start to finish, the process took over three years. Spreckley was admitted to hospital in January 1917 at the age of 33 and discharged in October 1920.

Two more success stories with surgery.

From the BBC

Injuries during WW I caused by trench warfare

A million British soldiers died in World War One, and double that amount came home injured. For many of those lucky enough to return, the wounds they had suffered in Europe would leave them permanently disfigured.

The trenches protected the bodies of soldiers, but in doing so it left their heads vulnerable to enemy fire. Soldiers would frequently stick their heads up above the trenches, exposing them to all manner of weapons.

At the start of the war, little consideration was given to the trauma of facial injuries. It came as something of a surprise that so many victims survived to the point of treatment. Escaping the war with your life was seen as reward enough. The advent of plastic surgery would radically change that perception.

Life after surgery

Many of Gillies’ patients would never overcome the psychological impact of their injuries.

Despite surgical advances, disfigurements remained profound, and patients often couldn’t face going out in public. Some continued to cover their faces despite surgical success.

Inside the hospital, mirrors were removed to stop them seeing their reflection and fainting. Given the time it took to carry out complex facial reconstruction, some patients would go years without properly seeing themselves in the mirror.

Nearby park benches were painted blue to designate them for men with facial injuries. However it was also done to warn local residents that the appearance of men using them may be distressing.

Some men could re-enter the workforce, but they were often too embarrassed to be in public and so would be hidden away in back-rooms.

Others became completely withdrawn, unable to face their wives, families and friends.

The man who fixed faces

The biggest killer on the battlefield and the cause of many facial injuries was shrapnel. Unlike the straight-line wounds inflicted by bullets, the twisted metal shards produced from a shrapnel blast could rip a face off.

Not only that, but the shrapnel's shape would often drag clothing and dirt into the wound. Improved medical care meant that more injured soldiers could be kept alive, but urgently dealing with such devastating injuries was a new challenge.

Harold Gillies was the man the British Army tasked with fixing these grisly wounds. Born in New Zealand, he studied medicine at Cambridge before joining the British Army Medical Corps at the outset of World War One.

Gillies was shocked by the injuries he saw in the field, and requested that the army set up their own plastic surgery unit.

Soon after, a specifically-designed hospital was opened in Sidcup. It treated 2,000 patients after the Battle of the Somme alone. Here Gillies would do some of his finest work.

Previously viewed with suspicion, facial reconstruction became an integral part of the post-war healing process. However, in a world before antibiotics, going under the knife for an experimental form of surgery posed as many risks as the trenches themselves.

Setbacks

A pioneer in his field, Gillies was keen to push the boundaries of plastic surgery further.

Many of the men sent to Sidcup had wounds far graver than any doctor had seen before. While they were surviving these injuries in greater numbers, the procedures used to treat them lagged behind.

Gillies was determined not just to restore function to the facial features of his patients, but to try to achieve an aesthetic result as well. This desire pushed Gillies towards further experimentation. But in a time before antibiotics, he was taking a big risk. What followed would teach Gillies a valuable lesson about the limits of the surgeons knife.

A pilot named Henry Lumley was admitted to Sidcup with horrific facial burns. To repair them, Gillies attempted to take a massive face shaped flap from his chest. The massive graft soon became infected, and unable to bear the trauma of surgery, Lumley died of heart failure.

This taught Gillies that plastic surgery had to be carried out in small stages rather than one big operation. It’s a lesson that still informs the field today.

What Gillies discovered

Gillies knew that when taking skin from one part of the body to another, it had to remain attached to survive. He also knew that doing so without antibiotics would be incredibly dangerous. How he did it would prove to be his greatest innovation.

His solution involved leaving the flesh attached at one end, rolling it into a tube and attaching the other end near to where the graft was needed. Called the tube pedicle, this method allowed Gillies to move tissue from A to B without worrying about infection. Living tissue was encased by the outer layer of skin which was waterproof and infection resistant. Gillies was able to leave these tubes in place for weeks at a time, with little risk. This greatly reduced the chances of something going wrong. Once a blood supply had grown into it from the new end, the original connection could be cut. From there the flesh could be swung into place.

See the entire article HERE